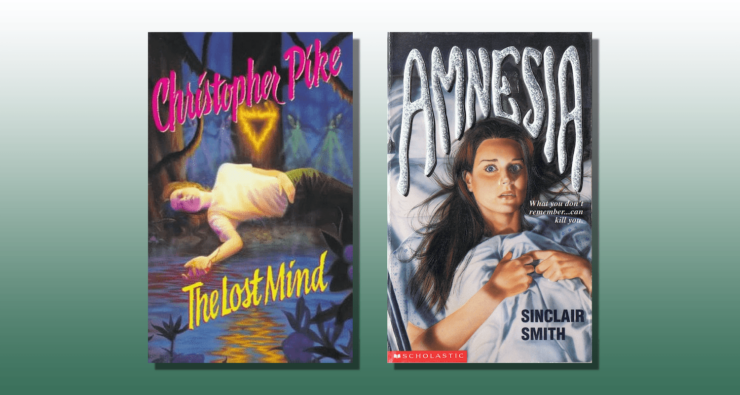

Amnesia and recovered memories have become an accidental theme of recent columns, from the repressed memories of High Tide and The Dead Lifeguard to the amnesia-faking antagonists of Sunburn and The Surfer. All in all, amnesia is ridiculously commonplace in ‘90s teen horror, with traumatic experiences blocking out whole chunks of characters’ memories or, in the case of those who fake their memory loss, providing a convenient excuse to avoid answering tricky questions, like “did you murder my great great grandfather?” While the protagonists of High Tide and The Dead Lifeguard think they remember most of what happened to them, with just a few isolated blind spots in their recollections, in Christopher Pike’s The Lost Mind (1995) and Sinclair Smith’s Amnesia (1996), Jennifer and Alicia both wake up with no idea who they are, what they’ve done, or how they’ve ended up where they find themselves. These girls’ quests to solve these questions and end their nightmares are central to The Lost Mind and Amnesia, with the act of recovering these memories taking center stage.

Pike’s The Lost Mind is told from a first-person perspective, immersing the reader in Jennifer Hobbs’s disorientation and confusion when she wakes up in the woods to find herself next to a dead body and covered in blood. As Jennifer looks at the body next to her, she searches her brain for any clues but discovers that “I didn’t recognize the young woman. I didn’t recognize my surroundings. Frantically, I tried to think of where I’d been last, who I’d been with. But nothing came to me. Nothing at all. Not even what day it was. What state I was in. What year it was … It was then I realized that I didn’t know who I was” (3). The murder weapon is near Jennifer’s outstretched hand when she wakes up and there is no sign of anyone other than the two of them at the scene. Jennifer is horrified and afraid, but almost immediately becomes coldly methodical in her next steps forward: she takes the murder weapon and sets off through the woods until she finds a road, with a car parked on the shoulder. She finds her purse in the front seat—including her driver’s license, from which she learns her name—and some spare clothes in the trunk, which she puts on after rinsing all that blood off in a nearby pool of water, careful not to get any evidence anywhere in the car. She stops at a phone booth and checks the phone book there to find her address, she gets a map of town from a pornography-browsing gas station attendant, and stops at the local Denny’s for some apple pie and a cup of coffee. She doesn’t go to the police, she doesn’t ask for help, and when the cops come calling the next day to tell Jennifer that her best friend Crystal was murdered and Jennifer was the last person seen with her, she tells them she has no idea what they’re talking about (which is, at least, a half truth). The cops’ investigation runs parallel to Jennifer’s own attempts to figure out who she is, what happened to her, and what she might have done. She doesn’t tell anyone that she has lost her memory except for her younger brother Ken (nicknamed Gator because he was a bitey baby) and unsurprisingly, Jennifer’s fabricated account of what happened and where she was the night before lead the cops to think she’s lying, covering up Crystal’s murder, and incredibly guilty.

Buy the Book

Knock Knock Open Wide

Since this is a Christopher Pike book, Jennifer begins figuring out the truth in her dreams. These dreams appear to be mystical memories of a past life or another person’s experiences, this time in Egypt, where a witch warns her against seeking for power and knowledge beyond her comprehension. The lines between Jennifer’s dreams and reality blur a bit here, because Crystal’s boyfriend Amir is from Egypt, and while there are brief discussions of how the police might be profiling and targeting Amir because of his nationality, race, and religion when they look to him as a suspect, Jennifer exoticizes and sexualizes Amir and the Egyptian culture of her dreams in ways that are also problematic.

As Jennifer gets closer to the truth, the lines between reality and fantasy blur even further, to the point where they are pretty much indistinguishable: as she learns through her dreams, each human soul is split into three different bodies before being sent to Earth, and while bringing two pieces of the same soul together can create an intense bond (soulmates), getting all three together is a recipe for disaster. Amir, Jennifer and Crystal each have a piece of a shared soul. Jennifer and Crystal have been friends since childhood, and when Crystal and Amir begin their relationship, it becomes an all-encompassing, sexually-charged romance. But eventually all three of them end up in the same room together, which was Amir’s plan all along. The lines between these three characters get even fuzzier, as Amir takes over Jennifer’s mind and uses her body to murder Crystal, then lets Jennifer come back to herself, where she wakes up to the nightmare in the woods. Amir’s alibi is rock solid, while Jennifer couldn’t look more guilty if she were actually trying, which makes sense because physically at least, she is the murderer. Jennifer intentionally overdoses on prescription drugs and threatens to kill Amir, tricking him into making the leap back into her body while she takes possession of his, a swap that results in Amir dying in Jennifer’s body, Jennifer living on in Amir’s body, and pretty much everyone believing that Jennifer murdered Crystal and then killed herself out of guilt and remorse (Jennifer leaves a note telling them this isn’t the case, but it isn’t very convincing, mostly running along the lines of “I can’t explain it but you just have to believe me,” which isn’t a particularly compelling argument, especially in the face of the evidence against Jennifer).

In the end, Jennifer once again knows who she is and is able to remember all that she has done, though that core identity has been complicated through the consciousness she has shared with Amir and, of course, even further through her occupation of his body. Jennifer doesn’t dig too deeply in terms of considering this gender identity, merely noting that “It was kind of weird not to be a girl anymore, but since that particular female body was, in the eyes of the law, guilty of murder, I didn’t mind having undergone such a radical cosmetic change” (205). In this case, necessity and the evasion of criminal prosecution are the mother of bodily transformation, which feels pretty unsatisfying, but presumably there would be some more complex negotiation of identity as Jennifer adjusts to life in this new body (one hopes). While Jennifer doesn’t tell her mother that she’s still alive in this new body, she does confide her secret in Gator while at her own funeral; he’s a bit skeptical, but she calls him by his nickname and is able to evade his snapping jaws when he tries to bite her, joyfully exclaiming that “You knew I was going to do that” (213). Gator’s convinced, no further questions asked and no additional explanation needed, however strange this new reality is.

Smith’s Amnesia is much less metaphysical than Pike’s novel. Alicia wakes up in a hospital bed with no memory of who she is or how she got there. She has a badly twisted ankle and a bump on the head, but those are the only clues she has to go on. The hospital staff only know her name because she was wearing a bracelet that said “Alicia” (which hardly seems foolproof, but it turns out to actually be her name, so that all works out). She has nightmares of an indistinct dark figure pursuing her and an overwhelming sense of fear that frequently borders on panic: she can’t remember just what it is that she’s afraid of, but her body and her subconscious are constantly sounding the alarm.

Quite frankly, the hospital where Alicia wakes up sucks. Nobody has time to sit and talk with her or answer any of her questions. The doctor provides Alicia with no information or follow-up treatment plan, but repeatedly tells Alicia to just calm down and relax, usually accompanied by what Alicia thinks of as an unnerving “game-show smile” (13). As Alicia is being discharged, still reeling from fear and trauma, the doctor’s final comment to Alicia is that maybe she should get a haircut when she gets home. When Alicia’s sister Marta turns up at the hospital to take her home, no one bothers to ask Marta for ID and there are apparently no bureaucratic safeguards or requirements in place to keep some random person from just wandering in off the street and leaving with a memory-challenged patient. When Alicia finds her way back to the hospital after her release looking for answers, the nurse at the front desk screams at her that she needs to leave, telling Alicia that she needs to call and make an appointment because “that’s the way it’s done” (121), and refuses to let Alicia speak with anyone or get any medical treatment. This doesn’t really instill any faith in the medical establishment and makes it pretty clear that if Alicia is going to be rescued, she’s going to have to rescue herself.

But back to Marta, Alicia’s mysterious sister who shows up out of the blue to take her beloved little sister home. When Marta shows up in Alicia’s hospital room, Alicia’s immediate, unfiltered response is one of “overwhelming terror” (17), which seems like a pretty dead giveaway that something is amiss, and should raise some red flags about sending Alicia off with this person. But as we’ve already established, the hospital sucks–they see Alicia out with a “somebody else’s problem now” sense of relief. As the girls head home, Marta tells Alicia a bit about herself, saying that Alicia has been in a coma for four months, she was injured in an accident that killed both of their parents, she doesn’t have any friends or social life, she loves liverwurst sandwiches and crossword puzzles, and she hates pizza. But even in these early moments, Marta’s version of Alicia begins to unravel at the edges. There aren’t any pictures of Alicia in the house, there are no personal mementos in her bedroom and all the clothes there are brand new, Alicia’s pretty sure she remembers kissing a cute dark-haired boy, and after trying her welcome home liverwurst sandwich, she knows for sure that she does NOT love liverwurst. Marta’s story occasionally changes or pivots—okay, Alicia did have friends but they’re a bad influence, they steal stuff, and they’re mad at Alicia because she didn’t share her last pre-amnesia score with them, so Marta’s just trying to keep Alicia safe from potentially dangerous people—but overall, Marta is pretty inflexible when it comes to how she sees the world and the version of her sister that she wants Alicia to be.

Marta is basically a kids’ version of Annie Wilkes. She uses ridiculous nonsense-type words instead of cursing, like “fiddle-faddle.” She’s solicitous to Alicia’s needs, to the point of keeping her confined to her room and literally feeding her, taking the fork and spoon from Alicia when she tries to eat by herself. This doting nature is punctuated by outbursts of rage, as Marta throws food against the wall, screams, and berates Alicia for not appreciating everything Marta does for her. Marta hides the only phone in the house and when she forgets one day and comes home to find Alicia trying to make a call (she wants to order a pizza), Marta becomes completely unhinged. Alicia sneaks into town once her ankle is healed, with the goal of buying groceries to help her sister out and relieve some of the tension, and when Alicia buys herself a canary to keep her company, Marta screams at Alicia for stealing money from the cupboard and opens all the first floor windows so the canary freezes to death overnight. The house is full of porcelain figurines and the day after Marta kills the bird, a porcelain figurine of a canary shows up in the spot where the cage had briefly stood, which opens up some horrifying possibilities (do ALL of the figures commemorate an animal or person Marta has killed? Because there are dozens of them, covering every surface of the house, and Marta’s real weird about people touching them) that go unexplored. When Alicia reads Marta’s diary and finds her sister’s ravings about how disappointed she is in Alicia and how much she hates her for not being the sister Marta wants her to be, Marta tells Alicia she’s going to kill her, pushes her down the basement stairs, locks her in, and then serves her the dead canary for dinner.

But locked in the basement, the quiet and her survival instinct work together to help Alicia remember who she is and what has happened to her. She finds herself beginning to draw to soothe herself and to pass the time, triggering a muscle memory response of herself as an artist. As this door unlocks, so do others, and soon Alicia knows the truth: Marta is not her sister. The two girls were friends as children, but Marta was possessive and jealous, exploding with rage any time Alicia made friends with other kids. When Alicia asked another girl to go on the carousel with her and Marta, Marta whacked the other kid in the head with a rock. Alicia’s parents moved her far away from Marta and Marta got some intensive psychotherapy, but her obsession with Alicia never really went away, and one day, she showed up at Alicia’s school, hid in the backseat of her car, and tried to abduct her. Alicia panicked in her attempt to get away from Marta and the resulting accident was the cause of her twisted ankle, her bumped head, and her lost memories. She hasn’t been in a coma, she does have a cute dark-haired boyfriend, and while her mother is dead, her dad is very much alive and has hired a private investigator to find Alicia (he does, though he gets brained with a frying pan by Marta as a reward for all that hard work and heroism). Alicia takes advantage of the detective’s thwarted rescue attempt to escape, running through the deserted town and an inexplicably unseasonal traveling carnival, with her dash across the darkened carousel jogging that long-suppressed rock memory. When Marta catches up with her, Alicia pushes Marta to the ground, knocks her unconscious, and curious townspeople drawn by the ruckus flood in to see what’s going on. Alicia is taken back to the hospital and reunited with her father and boyfriend, while Marta is detained by the police, though she continues to haunt Alicia’s dreams.

The representations of amnesia and repressed memories in ‘90s teen horror are diverse and complicated. Within the landscape of this ‘90s teen horror world, amnesia apparently happens ALL THE TIME, though despite its frequency, there seem to be few mental health interventions, structural support, or even screening processes to make sure people aren’t just faking it to get away with murder. The Lost Mind, Amnesia, and The Dead Lifeguard foreground the subjective terror and disorientation of not knowing who you are, what you’ve done, or how you fit into the world around you. While The Dead Lifeguard and High Tide consider the ways in which feelings of guilt (misplaced or not) may serve as psychological roadblocks, in Amnesia, Alicia’s blockage stems from childhood trauma, with Marta the first domino in a chain reaction that temporarily separates Alicia from herself. When mysticism and other planes of existence are added to the equation, like in The Lost Mind, all bets are off. To make things even worse, these teens don’t seem particularly well-protected or effectively cared for: in High Tide, Adam’s psychiatrist uses him as a guinea pig for radical experimental treatment, and his roommate Ian knows Adam didn’t kill his girlfriend Mitzi, but lets him keep on thinking he did and torturing himself with guilt so that he himself can get away with murder. In Amnesia, none of the medical professionals seem to really care all that much what happens to Alicia or what will happen to her after she’s released from the hospital. It’s like the cover tagline of Amnesia says: “What you don’t remember … can kill you.” So you’d better start remembering, because nobody else is coming to save you.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.